Tokyo is the safest city in the world. The Jigokudani monkey park, not so much. International tourists come from all over the world, and once they realize that from Nagaro station you have to get a specific and highly-sought-after bus, and once you get off that bus it’s a 2 mile walk straight up an incline, they get pissy. You’re going to hear a lot of swear words in a multiplicity of languages and people stop moving aside on the path.

Especially in winter, because that path is covered in snow and ice. Sweetest thing we saw on the path was a tall elderly man and his short wife, looking and speaking Nordic. The tiny handrail on the turning slope didn’t reach this guy’s knees, but he was trying to use it because they were both clearly terrified.

Below them a group of Middle-Eastern-looking men spoke to each other, turned, and two of them went back up that treacherous slope and said one English word: Sir. And each held out a hand to him.

They got him down. We got up, although we had a bad moment when we thought we were going to have to carry our entire luggage up the whole way. Turns out you can pay to leave luggage at the information booth, but the little girl working there was not forthcoming with this info. It is hard to tell ages on face types one doesn’t see everyday, but I put her below 15 for sure. And bored out of her mind. But she saved our lives when she agreed to watch our bags for 500 yen.

Up we went, and as we ascended I looked at the faces of those descending. They looked happy.

“We’re gonna see monkeys,” I said to Amelia.

She half-grunted, half-gasped. We were on a steep part.

Like the giant Buddha, the monkeys were on Amelia’s bucket list, and halfway up the vertical two miles, I believe she may have been regretting some life choices. But there we were.

In the snow and ice I kept seeing tiny yellow circles. I am one of those weirdos who picks things up, but not until I’m sure what they are. At the bottom of the hill, a bunch of Romanians were selling crampons, plastic tie-ins to cover tennis shoes and let you dig into the snow. The little yellow circles were the tops of the embedded studs from those high-quality products we had decided not to buy.

We saw our first monkey even before we got to the park. We saw our second monkey 12 seconds later.

“No matter what, Amelia, we did it! We saw monkeys!” I shouted in jubilation.

“Ufffmopht,” Amelia said, gripping the hand rail. We were at the top.

We saw monkeys. Big grandfather monkeys, teenage monkeys, baby monkeys, mama monkeys with babies on their backs. There were roughly three people for every monkey, and some of them had massive camera lenses. I got tired of taking photos of monkeys sitting under these lenses while people trained them on far off slopes. I laughed at one guy who was photographing a monkey sitting coquettishly on a stone in the hot steam of the spring, while next to him another monkey touched the pompom on his hat. Turning from this scene, I nearly tripped on a monkey crossing the bridge behind me.

“Sorry,” I muttered, but that little guy only spoke Japanese.

We had our fill over an hour and a half. Monkeys are cool. Monkeys are cute. They came running when a staff member went out with a bucket of treats and attracted them to the hot spring where 400 photographers waited. It was like watching the cows come in.

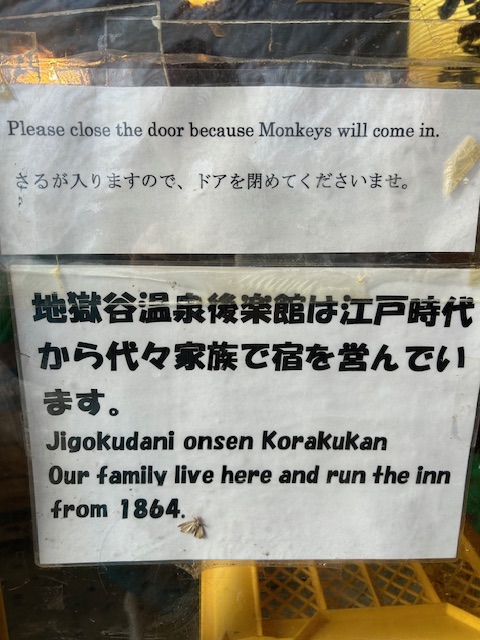

Amelia and I decided not to go to the human onsen there. Sharing human water is one thing, but with monkeys is another. We stopped at an inn where a kindly elderly man would make us hot cocoa for 500 yen. The sign said his family had been running the place for 9 generations.

We stepped across the breezeway, took off our shoes, and sat down in the scenic dining room hanging off the back of the mountain. I got out the apples, cheese, and crackers we had brought for lunch, and Amelia said, “I think we have to go back across to get the cocoa.”

Popping on my shoes, I crossed the breezeway and the kindly man said “No no I bring.”

At the entryway, I took off my shoes, slid the door open and closed–and it flew out of my hand.

A rather portly monkey entered. Astonished I turned and blocked her way toward our table. We made eye contact, something all the signs tell you not to do. I said, in my most reasonable storyteller talking to kindergartners voice, “You need to leave now.” The monkey looked me in the eye. I stomped my foot, and the monkey cocked her head at me. The thought bubble above her head said, “Nuisance, not threat.”

The thought bubble above my head was just forming, in the shape of a headline: first stupid tourist death reported at monkey park in showdown over table space at local diner.

The monkey sidestepped me with casual disdain and headed for Amelia, who had been filming me coming in but dropped her phone when she saw the monkey. I have a picture seared in my mind of Amelia, recoiling backwards against the dining room windows, as the monkey reached our table in two mighty bounds, sat down atop it, and picked up a package of crackers.

I reached the table in three steps. “Those are plastic! You’ll hurt yourself!” I said to the monkey, reaching for the crackers.

She smacked me. Like a mother might do a fractious toddler. Not harm, not intent to be mean, just “stop that.” Then she picked up one of our apples and bit into it, picked the other one up in her hand, and with this bounty exited the room in three leaps.

I felt a pang of loss. They had been very good apples and I only got one bite. From the only other family in the room, a woman in pink hijab said, in a tone I didn’t consider entirely friendly, “That’s why they tell you to close the door.”

I glared at her. She had a toddler smaller than the monkey, so likely she was in full tiger mama mode, but I swallowed my retort: They don’t tell you the part where monkeys rip them out of your hands, madam. Those little bastards are strong.

Amelia and I made do with cheese and the remaining crackers, plus the delicious cocoa the man brought a moment later. When we exited the inn, that same monkey was sitting outside, looking as if butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth. Just waiting.

I like to picture her entering her home with the apples: Get out the fruit knives, Bert! Lunch is ready!

Alternatively, she went straight round the back to the kitchen of the inn, where the kindly old man gave her 200 yen for the apples and put dumplings on the menu.

We inched our way downhill. The only thing worse than uphill ice is downhill ice. We slid on one slope but never fell. At the bottom that same bored child was watching the shop full of monkey trinkets and the tourists with equal disdain.

On impulse, I typed into google translate: Thank you. We had a lovely day and would not have made it if we had to carry our luggage. You probably have souvenir money from America, but if not, would you like some?

She stared at the phone, then her eyes lit up as she looked at me. Honestly, I don’t think it was the offer of an American dollar. It was that someone saw her.

She brought my bags, I gave her the dollar, explained it was roughly 100 yen (more like 150 but I can’t say 150 in Japanese) and she literally squealed as she beamed. As people looked around–maybe seeing her for the first time–she tucked it into her pocket. We bowed to each other, Amelia got her son a t-shirt, and off we went, replete with adventure.

I hadn’t seen the thieving monkey lurking by the door, but I had seen the bored teen who just needed a boost. And if you are robbed, remember: give something away afterward and you will feel better.