After our second breakfast (Uhm, as in second day in Pitlochry, not in the Hobbit sense) we said goodbye to the lovely waitress, and gave her two of Jack’s and my CD of Scottish songs, one for Bridget and Peter, one for her.

We also cleared our bar bill.

Off to Aberlemno to see some of Scotland’s best standing stones. Also called menhirs, they’re from the Bronze Age, and people are STILL debating whether they are historic records, religious symbols, or the first computers. (Predicting weather patterns and such by calculating the sun and shadow movements, something like that)

We’ve taken many people to see these stones over the years, so we know that they don’t expect one thing we enjoy watching them figure out. The Aberlemno stones are FUNNY. There’s a centaur carrying a plant, representing medicine. Herbalists have said for centuries that it looks like dried mullein still on the stalk. There’s a soldier with a raven on his face. (You can see both in the photo above.) Technically this probably represents the massive deaths at the battle of Dun Nechtan in 685. Pictish forces under Brude MacBeli defeated the Northumbrian King Ecgfrith and his army. (That seems to be the battle depicted on the stone, and Ecgfrith may be the guy the raven is taking out.) But it also gave rise to a weird story that the Picts magically controlled ravens who attacked the invaders, giving rise to the growing fear of those fierce little blue-painted guys north of that wall. (Hadrian built his famous wall to keep the Picts out.)

Anyway, the more you look at the stones the crazier the stories get. Plus there are a few symbols no one has yet figured out the meaning of; these recur on many stones across Scotland and have been given names like the mirror and the comb, just because that’s what they look like. There’s no indication that these are female symbols.

But we can never look at these mysterious designs without thinking of Marianna Lines, an American artist who lived near us in Fife and was an expert on Pictish symbols and standing stones. She died more than a decade ago, but we always send a thank you to God for her life when we stand in front of the Aberlemno stones.

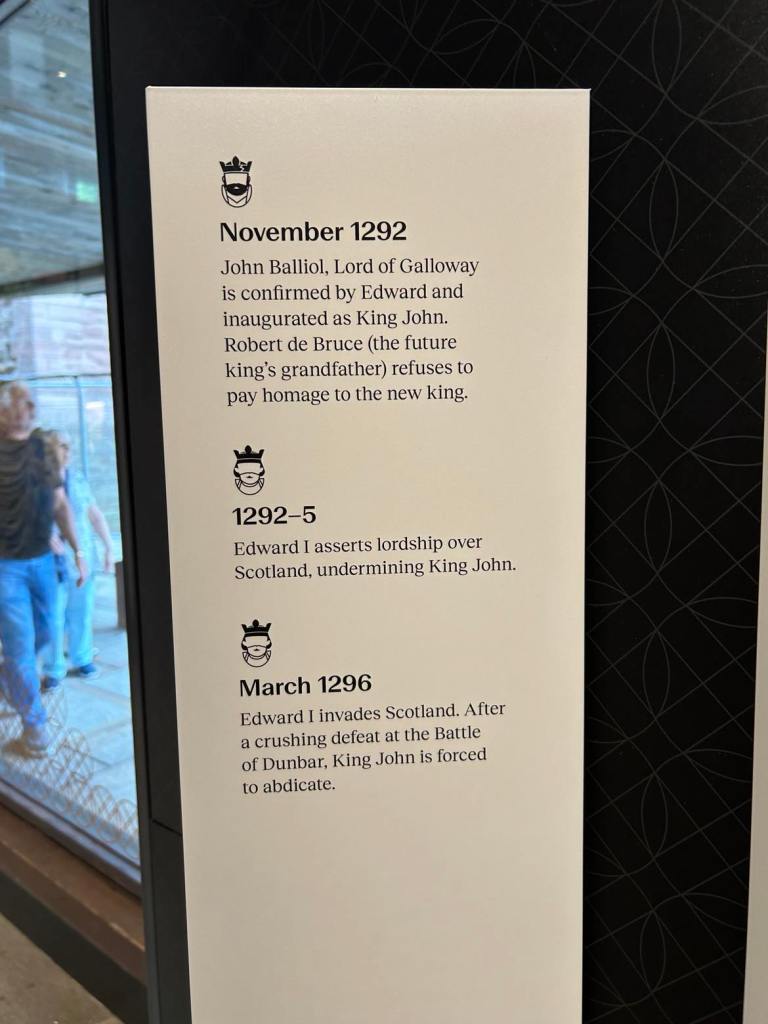

From there we made an unscheduled stop at Arbroath Abbey, mostly because it’s such an important historic point in Scottish (and indeed European and American) history. If you’ve seen the movie The Winter King, you know what a bastard Robert the Bruce actually was, but that he was the better of two horrible arses both trying to rule Scotland as the 1200s turned into the 1300s. Edward was King of England, and he let Edward Balliol rule Scotland as King because Eddie the Scot was loyal (read: subservient) to Eddie the English; Bruce was fighting Balliol the whole time he was on the throne.

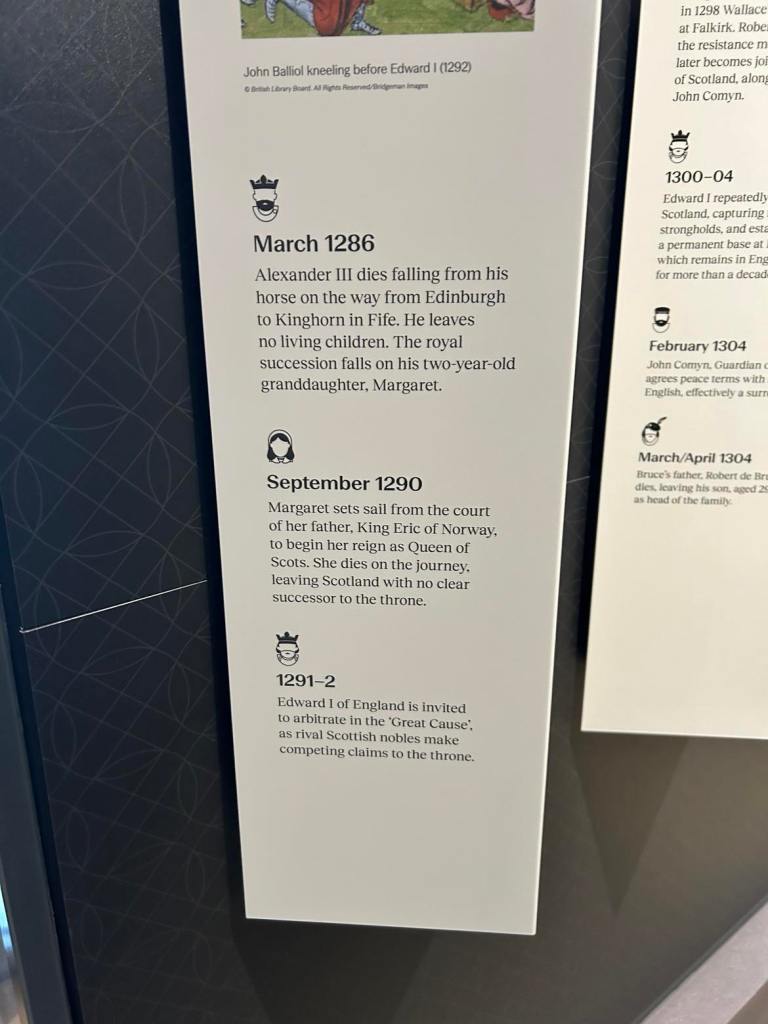

When Balliol senior died his son John ascended with help from good ol’ English Ed, but he lasted like twenty minutes, to be replaced by his cousin, also named John. (So they didn’t have to change the letterheads,) The reason there were at least two strong claimants to the Scottish throne is complicated but fascinating, and includes a famous ballad about Margaret of Norway (not historically accurate but lovely all the same). You can google the Second War of Scottish Independence or read the interpretive plaques above. (There were a LOT of Scottish independence wars.) Also what the plaque doesn’t say about Alexander and that fateful horse ride was that he was making a booty call. He was literally on his way to see his mistress, even though his courtiers with him said it was a terrible rainy night and he shouldn’t go. That’s how he died. That’s how history is made. He set in motion a chain of events that left Scotland in dire straits for about 25 years.

Short version of how Bruce finally became king: Robert the Bruce tricked John Comyn, Eddie-the-Scot’s nephew and heir apparent endorsed by English Eddie, into meeting in a church to talk peace terms–then stabbed him dead and declared himself king in front of the nobles assembled for the meeting.

Now here’s the fun part: the whole time Bruce had declared himself king of whatever he could claim from the north and tried to take out his rivals, he was a pretty bad ruler. Scotland was suffering famine because of the men being forced to go for soldiers, ruining crops and production not to mention requisitioning the work horses people needed to farm, plus Scotland had a long spate of terrible weather (which is saying something for Scotland). Worse, the plague had hit. People were broke, tired, hungry, and sick.

What did Bruce do after he killed his rival in a church? Unite the northern and southern areas? Tell people he had grain in storage for seed? Nope. Told everybody the most important thing for Scotland was for him to be crowned the final and definitive king because then they’d be free from English tyranny. He’d get around to helping with the harvest and all that after he was securely on the throne with the English threat removed; send your sons, we’re going after English Ed.

Yeah, that was a little too much for the nobles who had helped put Bruce on the throne, (read: who knew what he was going to do at that church-and-dagger meeting) so they did something that helped found America, changed the course of European history, and scared the Pope and a whole bunch of other big shots nearly to death. On April 6, 1320 they hauled Bruce out into the courtyard of Arbroath Abbey, sat him down at a camp table, and made him sign a letter carefully prepared for the occasion. The sense of threat at making Bruce sign in a field was intentional; he was signing the Declaration of Arbroath.

The Declaration of Arbroath was probably drafted by an abbot named Bernard, at the behest of most of the Scots nobles. They had had enough of all the war and famine. The letter asked the pope to recognize Bruce as the rightful Scottish king. Then it said, more or less, and we the nobles will make sure he behaves well and if he doesn’t he will find out quickly that he actually answers to us, because we have put him on that there throne he coveted so badly. So if he doesn’t behave well toward us, we’ll be in touch, Mr. Pope.

You should read the declaration; it is a masterpiece. And Thomas Jefferson stole pieces of its wording, as well as its foundational idea, to write the American Declaration of Independence.

The abbey seemed to fascinate and sober everyone at the same time. Several people made comments paralleling Scotland’s troubled divisions to modern-times America. Which led to one of the first political arguments of the trip, as Lulu and Harry engaged. Good points were made, honest questions asked, and freedom to argue rang through the van until somebody broke out some millionaire shortbread and we all got too much caramel in our mouths to keep talking. When all the people can eat, there is sweet peace.

Our next stop was Dundee, Scotland’s answer to Pittsburgh. It’s got some culture spots (and an awesome bakery) but mostly it’s a seedy little working class town. Zahnke party of three headed for the Discovery, Harry and Andrea went to the Victoria and Albert museum, Maria sought donuts at the specialty bakery, and Cassidy stared in horror at the driech city and said she’s stay on the bus.

I know from my many times telling stories at the Dundee library that there’s a dragon carved on one of the streets, so I raced to visit him and fit in a few thrift stores. (Even these couldn’t entice Cassidy away from the safety of the van!)

Andrea had a good moment at the train station near the museum. We had been encouraging all the musicians on the trip to take part in ongoing ceilidhs, but Andrea declared herself on vacation from her position as church pianist. The piano at the train station enticed her and she played a few pieces, to the delight of a few passersby.

When we left, Cassidy summed up the opinions of the group: okay, now we’ve seen working modern Scotland, but we liked the castles and history version better.

Off to Keavil House hotel in Dunfermline we went, but with one more stop to visit an old friend. Duncan Williamson’s grave is in Strathmiglo (also the home of the Johnny Cash family’s ancestors). We always put a rock on the grave and say hey, buddy; he’s another voice we miss in the world.

And there was a nice quiet dinner replete with steak and kidney pie in the sunny solarium-dining room, and there was sleep, and that was the ninth day.