Dear Miss Ten Boom –

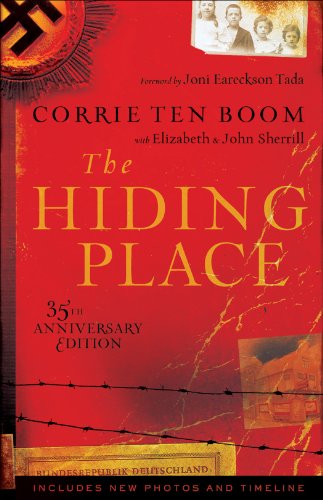

I read The Hiding Place for the first time when I was much too young to understand its full implications. When I began teaching sociology, I used it to introduce the Holocaust to sheltered students in a religious institution.

And now I find myself picking it up to read again, alongside Tim Alberta’s The Kingdom, The Power, and the Glory, and the Old Testament books First and Second Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles. They all deal with regime change, and the struggles between good and evil.

These days, we have Wicked taking Hollywood by storm, but for the most part, there are good guys and bad guys in good versus evil plots, and they are easy to tell apart.

Your book, your life story, there in Holland being a nice spinster watchmaker in your fifties with your family business, suddenly hiding people the Nazis were trying to kill, it had good and evil. But rereading it, I find places where it got tricky to tell them apart.

I remember a story from your book: someone from the resistance came to your watch shop to ask for significant names. They wanted to kill those people. They wanted you to help them set it up. And you said no. And agonized over it.

It is getting tricky, and likely will get trickier, to figure out good and evil in the United States right now. White is black and black is white, right is wrong and wrong is right. The liberal elites want to build a super-government everyone has to obey, but the right wingers are doing it, using threats of violence. It’s all getting a bit tricky, Ms. Ten Boom.

When I read The Hiding Place again recently, I saw something else in it: your loneliness, and your singlemindedness. You missed your sister. You didn’t know what to say about what was happening to you. You tried to be nice to some Somalian women in the rescue hospital who didn’t know anything about what was going on and they clearly viewed you as a threat and you didn’t know what to do with that. How hard was it to know what to do, Corrie? Your book resonates with getting to keep your Bible in the prison, reading, praying, holding out hope against hate. What did it feel like, every day, making decisions to not hate the people who were showing you hate, knowing you had the moral high ground, but were considered the criminal? How simple can we make these decision?

What did you worry about when you told the resistance people you wouldn’t help them kill Nazis? Did you fear for the little collection of Jewish people hiding in your house? Did you know all your neighbors knew, but still wave to them each morning? Did they wave back?

Tell us where to put our feet, Ms. Ten Boom, when our allegiance is not to America, but to God, and we don’t think those two names are synonymous. How do we live?

Thanks for listening. I may come back to you in the coming months. It’s kinda hard to sort through everything right now, and surely that is intentional. Big power displays to cow and intimidate, followed by the real meanness. What did you pray for, Ms. Ten Boom? How did you keep your head when those around you were losing theirs, or offering up their neighbors’ for a fee?

Sincerely,

A Christian in America

I thought about blogging this book in the wake of the Tree of Life Synagogue shootings, but wanted to wait a week.

I thought about blogging this book in the wake of the Tree of Life Synagogue shootings, but wanted to wait a week.